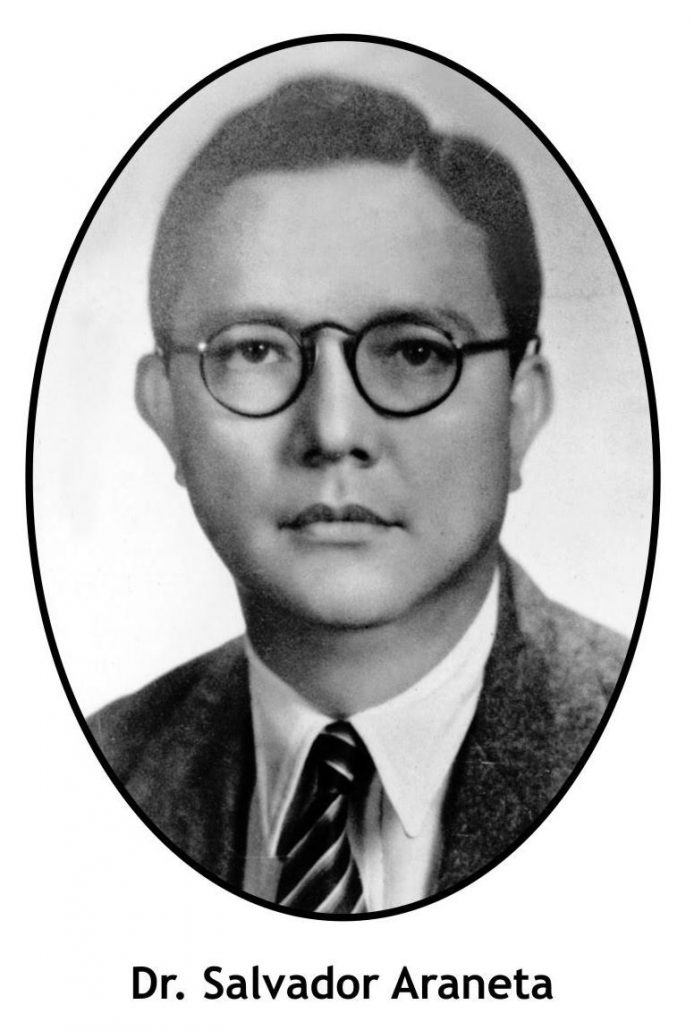

SALVADOR ARANETA

SALVADOR ARANETA

Voice in the Wilderness, A Short Biography

In his introduction of the book on the Bayanikasan Constitution by Dr. Salvador Araneta, Dr. Alejandro R. Roces said there is something of Pilosopong Tasyo in Araneta.

The admonitions of Jose Rizal’s proverbial philosopher and Araneta’s views and ideas were neither understood nor appreciated by the people of their respective eras. Their observations and advice were met with indifference or derision. Their brilliant thoughts were deemed impractical, or worse, crazy.

Roces said that although Araneta’’s Bayanikasan Constitution was addressed to his generation, it was to be used in one to two decades. Roces said Araneta’s “plan for tomorrow is ready today, but it is Today that is not ready for his plan for Tomorrow.”

Like Pilosopong Tasyo, Araneta was an ardent student. He was a lawyer, an economist, an educator, a pioneer in aviation and industry, a public servant, and a Constitutional Convention delegate (both in the 1934-1935 and 1971-1972 Conventions) who also was hard at work in writing down his vision for future generations in a new and an out-of-the-box Constitution.

The time has come when we should look at Araneta’s work, done almost half a century ago, to prepare the Philippines to emerge as a strong and independent nation, a model of democracy, with peace and prosperity for all its citizens.

Araneta looked even further to an entire world where the brotherhood of man was a way of living and thinking.

Araneta’s father, Gregorio, taught him that what was most important in life was not the amount of money one can amass, but the ideas he can propagate that would bring a better life for others and not just for one’s family.

Araneta shared the tools he learned from Harvard with his students at the Araneta Institute of Agriculture, now De La Salle Araneta University. He admonished his students not simply to memorize, but to study further and formulate their own opinions. He reminded them to observe, and read, read read. He reminded them of the importance of imagination as without imagination, he said there would be no invention and there would be no new ways of doing things.

He told them never to stop asking “why” and they have to be prepared to work hard, be on the giving side, and not the other way around. This explains why he advised his graduates: “Do not be a job seeker, but a job giver. Let each day count, have a vision and a mission in life. It would be wise to be proficient in English and learn Chinese, Japanese, or Arabic.”

Furthermore, Araneta emphasized: “Stick to integrity and do not count on luck or political influence. Be the creators of circumstance and not the result of it.”

The Question of Real Independence

Araneta was well prepared for a career as a lawyer. In fact, he was no ordinary lawyer as he was admitted to the Bar of Washington, D.C. on Feb. 27, 1938 at the recommendation of Governor General Frank Murphy.

Araneta was also an ardent advocate of true independence and he yearned for a country freed from “the shackles of economic servitude from foreign interests.”

He made real independence his goal in life. He was convinced that a government of the people could only be achieved if “the control and enjoyment of economic forces of the nation were in the hands of its citizens.”

This was of importance to Araneta because the life of a nation should last forever. Araneta said that the Filipinos must be ready to assert and vindicate their rights.

Real independence may well start with the kind of independence that the United States was prepared to grant the Philippines. A topic of great concern was the issue of the re-examination of Philippine Independence, as well as Philippine-American Reciprocity. Araneta told President Quezon that we would get less autonomy after independence and that our independence would be one only on paper.

Araneta clarified that in the plebiscite of 1935, three different issues – the Constitution, the Commonwealth and Independence – were submitted to the people. The defect was while there were three issues involved, the people were given only a single vote to decide on three issues.

Araneta’s stand on the question of re-examination was that the Act should be examined from four angles: its economic provisions, the provision limiting immigration during the period before independence with the total banning after independence, providing autonomy during the Commonwealth period and providing the kind of independence we would be granted after independence, including answering the question of military and naval bases. (To be continued/PN)