Araneta on Roxas the Economist and Roxas the President

Araneta on Roxas the Economist and Roxas the President

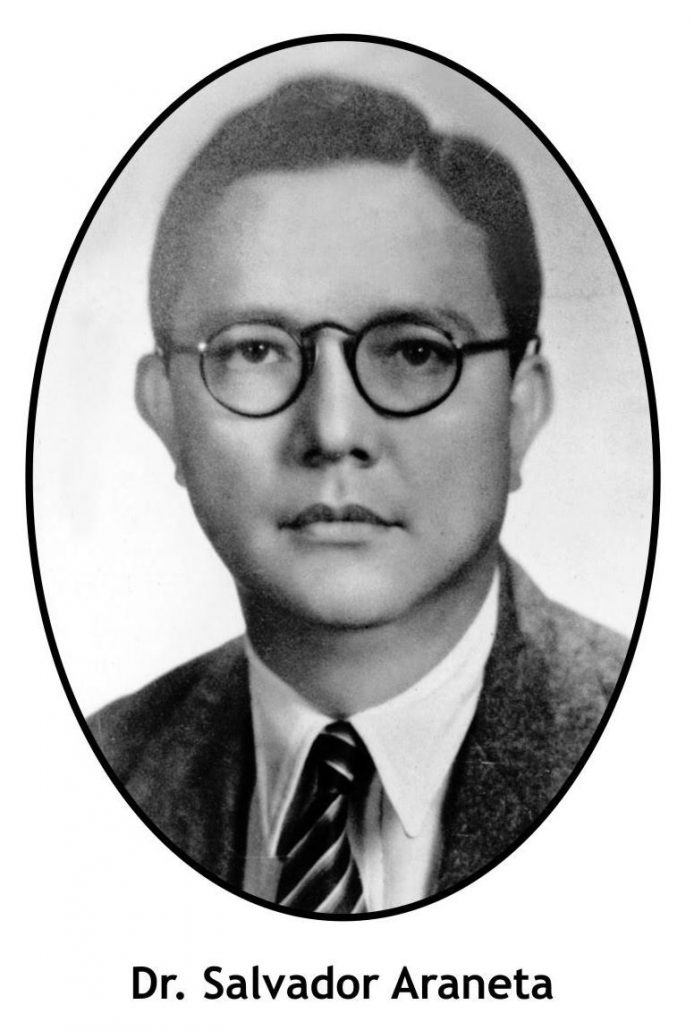

Dr. Salvador Araneta made a distinction between Manuel Roxas the economist and Manuel Roxas the President.

Roxas and Araneta became two poles apart. The former was for Parity and the Bell Trade Act while the latter was vehemently against both pieces of legislation.

In 1936, Roxas the economist expressed his views in a speech before a convocation at the Ateneo de Manila that Philippine independence may succeed without free trade.

Ten years later, Roxas the President changed his view. He started to advocate the acceptance of the Bell Trade Act on the theory that without free trade with America, we were doomed to disaster.

Roxas said delaying the acceptance was equivalent to gambling the lives of the Filipinos and that all the dreams and longing for democracy, of social security, of agrarian reform, of prosperity and happiness were tied to our acceptance of the Bell Trade Act.

What was deplorable was that in the early 1930s when Roxas was Speaker of the House, he inaugurated his crusade for a Bagong Katipunan aimed at fostering a new Philippine ideology that combined Protectionism, Patriotism and Economic Independence. As President, he was doing a 180-degree turnabout.

One of the arguments presented by Roxas was that capital follows the flag. Not so, according to Araneta in the case of the Philippines. The propaganda of Roxas was a mere myth. The truth was that we had parity in 1898, and again free trade since 1909. However, the Philippines had very few industries and could boast of no industry in particular.

Our natural resources remained undeveloped and only a small amount of American capital came to the Philippines. Under closer scrutiny, a great bulk of the so-called investments was actually accumulated wealth created in the Philippines.

On the other hand, the United States invested in Latin America in the form of government bonds and direct investments to the tune of billions of dollars without strings of the likes of the Bell Trade Act attached.

Was it the hostility of Filipinos towards American investments or the lack of giving American incentives to bring in capital and machinery into the country that prevented American investments from flowing into the Philippines?

With free trade, why come to the Philippines when the Americans could just as easily manufacture goods in the United States with the same overhead and sell their products in the free market of the Philippines?

The only hostility, according to Araneta, was that shown by the Osmeñas, the Quezons, and the Roxases of those days against American trusts and companies like Firestone.

Firestone demanded the amendment of our land laws which limited the acquisition of public lands, either by Americans or Filipinos, to 1024 hectares. Firestone wanted more.

What did our government do that would show hostility?

It simply enacted these three laws: one limited the acquisition of public agricultural lands, another limited the holdings of a person in more than one mining company, and a third law withdrew from private exploitation our oil resources.

The other laws mentioned by President Roxas referred to the mining law limiting development to one vein in a gold claim, and the law on expropriation. However, Araneta reminded Roxas that those laws were of American origin.

When Roxas was elected President in April 1946, he had to act on the Bell Trade Act. Araneta saw three forces pinning Roxas down to advocate its acceptance. One factor was pressure from the country’s sugar interests which saw the act as their salvation. Another consideration was Roxas’ wish to obtain American financial assistance for his government. The third factor was retaining the friendship of American officials who had helped to whitewash him of charges of wartime collaboration with the Japanese.

Araneta observed that “President Roxas became the foremost Filipino champion of the Act.”

On the matter of borrowing from the United States, Roxas feared that by not accepting the Trade Act, he would not be able to borrow from the United States. On the contrary, money had been lent to other countries without parity and without free trade.

Araneta cited England, who borrowed several billions of dollars. Brazil also borrowed substantially for the development of its steel industry, without parity, free trade and currency control. After the depreciation of its currency, France also obtained a loan without surrendering any of its economic liberties. (To be continued)/PN