WHAT I like most about Janeth Deza Demegillo’s reading of “Padre Olan” is her focus on the otherwise neglected and ignored women of the story. I think I did a pretty good job exalting the women in my writing of the story. But often, readers only focus their attention to the (male) leads. But see how reading gets more exciting when you try to focus on other things — the secondary (female) characters, in this case?

*

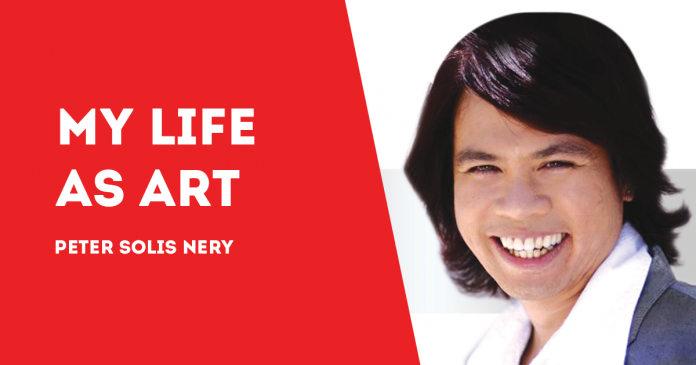

Double doctorate Demegillo is an educator and entrepreneur with a private consulting business in Koronadal City, South Cotabato. A dedicated wife and mother, who is also active in civic affairs, she is the recipient of the 2018 Special Peter’s Prize for Excellence in Cultural Dissemination, among many other awards.

*

The Strong and Servile Women in a PSN Masterpiece

A feminist reading in the men’s world of “Si Padre Olan kag ang Dios”

by Janeth Deza Demegillo

*

“Si Padre Olan kag ang Dios” by the celebrated Hiligaynon writer Peter Solis Nery is a literary masterpiece the significant details of which never leave a gap in the mind.

Passionately crafted (as evidenced in the very nuanced use of the Western Visayas region’s local color) and written in the beautiful Hiligaynon language of the Nery variety, this Palanca Awards first prize-winning story presents a truthful human experience by using artistic structure, form, techniques, and style as efficient vehicles of expressing a wide range of ideas, and the whole gamut of human emotion. It is a rare cultural and literary artifact that both preserves the Hiligaynon language, and celebrates the Ilonggo culture.

As a piece of literature, the story’s language and craftsmanship delighted me the most. But it also gave me a lot of insights, and has even transported me to a journey of my own faith, vigilance, life struggles, hope, values, advocacies, political views, supernatural beliefs, as well as personal pain and pleasure as I tried to identify, or relate, with every character that contributed to the plot.

On my first reading of the story years ago, I enjoyed it most for its language that touched base with several levels of usage. There’s the literary language stylized to depict the various elements like setting, characterization, point of view, and plot.

But that language progresses and shifts to colloquial and provincialism (as when the characters speak), and goes to high and formal literary that is almost poetry (if it is not yet already) when the writer assumes the authorial voice to describe and narrate the events in the story. On the whole, PSN played the elements of the story perfectly. The setting contains images that set the mood, and lurches towards the powerful and well-considered characterization.

On rereading the story years later, something happened. Perhaps because I was no longer excited about the novelty of the plot, my attention was actually drawn to the women in the story. If my first impression of the story was focused on the male important characters who embodied the conflicts of man against man (Padre Olan versus Don Beato and the Knight of Columbus; or Padre Olan versus Father Fritz and Archbishop Lagdameo), man against nature (people versus the long drought), and man against himself (Padre Olan and his doubts), this time around, I was pleasantly surprised to see, and understand, the contrast of the women characters Paquita, the convent help; and Alicia, the president of the Catholic Women’s League.

They are character studies that really appeal to me as a feminist because they are present in the story as archetypes of the women in our society today: Inday Alice is vocal about her personal stand and opinion as she leads the CWL, and Nang Paquit is reserved and content in her servile role and function as the convent help.

Alicia is evocative of the women who are advocates of change, and are loud about it. The Alicias of today are heedful of the various issues affecting the society, and they act upon these issues for a resolution. The Alicias support the cause of their partners: they may seem submissive, yet are really resolute; they are talkers, but also listeners at the same time.

The Alicias are leaders, and equals of men in decision-making. They are not merely relegated to the homes and the household chores; they are simply not the manufacturers of babies; nor do they consider themselves as second class citizens, or the mere second sex.

The Alicias are the women who have the butts, the guts, and buffs, maybe even the bluffs. They are the women who fairly and squarely face the vicissitudes of life, the realities of existence, and the challenges of time. They are the women who have evolved from being mere facets to become valuable assets. And, regardless of the generation they belong, the Alicias allude to the strong, decisive, and empowered women.

But there are as many (if not more) Paquitas as there are Alicias in today’s Philippine society. The Paquitas are desirous of change, yet have no spunk or fearlessness to unwrap their true courage.

The Paquitas are those women who simply wait and see, but do not actively partake in the making of history. The Paquitas are happy to go along with change, but are afraid to execute its fulfilment. These are the women who totally submit to authorities, and may consider themselves inferior over their male counterparts, and, of course, their bosses as well.

The Paquits are women who plow the culture of silence even when the effects are adverse on them. These are the women who are silenced by poverty, and are intimidated by riches and power. And, to some extreme occasions, the Paquits are the women who only wait to benefit from the feat of other women.

Inday Alice and Nang Paquit are just minor characters or bit players in the male-dominated world of PSN’s “Si Padre Olan kag ang Dios”, but their characterization is meaningful and deeply thought out, which renders the story to be even more textured, relevant, and fully realized; which, in turn, is another clear indication why Peter Solis Nery, the PSN, is master storyteller extraordinaire above all the others./PN