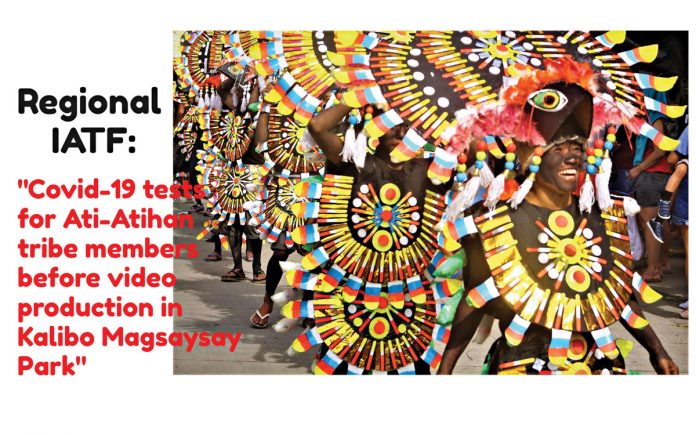

KALIBO, Aklan – For this year’s Ati-Atihan Festival, organizers planned to make a video production of the performances of the participating tribes at the Kalibo Magsaysay Park then stream these via the internet or social media instead of letting the tribes perform live on the streets due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

However, the conditions set by the regional inter-agency task force on COVID-19 for the video production were too logistically challenging, according to festival organizers. Thus they scrapped the video production plan.

“The production team will just gather old videos of the Ati-Atihan for airing on Jan. 16 and 17 instead of physically gathering the tribes and record their performances on video,” said Sangguniang Bayan member Ronald Marte.

What were the conditions set by the regional inter-agency task force?

One, for all the drummers and dancers of 23 Ati-Atihan tribes to take COVID-19 tests and be negative for the disease.

Two, observe two weeks of quarantine before the video production.

According to Marte, the local government may not be able to shoulder the cost of the COVID-19 tests and the expenses that two weeks of quarantining all performers and drummers would entail.

He also pointed out the very challenging timeline for this.

In setting these conditions, the regional task force pointed out that an outbreak of COVID-19 as a result of “high-risk activities” could strain hospitals and healthcare workers.

There were reports that the local government already released P15,000 subsidy to each tribe for video shoot preparations, including the repair of their old Ati-Atihan costumes.

Meanwhile, Maranatha Vargas, head of the Public Affairs Information and Communication Division (PAIAD), said the Ati-Atihan “fun bike ride” was also cancelled.

“Ati-Atihan” means “to imitate Ati”, the local name of the Aeta people, the first settlers of Panay Island.

The festivity was originally a pagan celebration to commemorate the Barter of Panay, where the Aeta accepted gifts from Bornean chieftains called Datu who fled with their families to escape a tyrannical ruler, in exchange for being allowed to dwell in the Aeta lands. They celebrated with dancing and music, with the Borneans having painted their bodies with soot to show their gratefulness and camaraderie with the Aeta who had dark skin.

Later on, the festivity was given a different meaning by the church by celebrating the acceptance of Christianity, as symbolized by carrying an image of the Holy Child or Infant Jesus during the procession.

The festival consists of religious processions and street-parades, showcasing themed floats, dancing groups wearing colorful costumes, marching bands, and people sporting face and body paints./PN