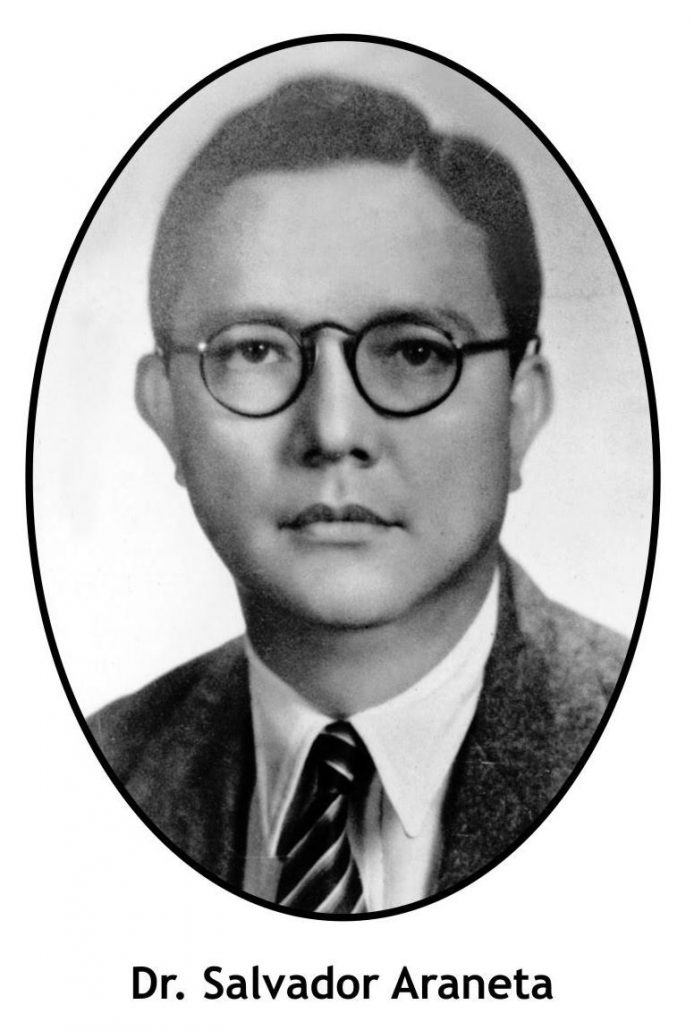

SALVADOR Araneta was not xenophobic. He was just against the condition that prevailed at that time, wherein only 20 percent to 25 percent of the retail trade was in the hands of the Filipinos.

SALVADOR Araneta was not xenophobic. He was just against the condition that prevailed at that time, wherein only 20 percent to 25 percent of the retail trade was in the hands of the Filipinos.

This had to change. The rest was held by the Chinese and the Japanese. The price of basic commodities were controlled by foreigners particularly, rice. Moreover, foreign traders were not interested in distributing locally manufactured goods and as a result, the local manufacturers could not expand their business.

Araneta saw the retail trade as a source of growth for local manufacturers, as well as investments and a source of foreign exchange reserve. He stressed the importance of local production of goods for local consumption. At that time, we only had a population of probably less than 18 million people.

He said that, “The populace should understand that we should be self-sufficient in food and in producing construction materials as well as household items.”

Towards this end, Araneta and several businessmen formed the National Economic Protectionism Association or NEPA before the war. They promoted “Buy Filipino First.”

Likewise, after the war, Araneta gave his all in his fight against Parity Rights that he called “Busabos na Parity.” These were the rights that the United States demanded and got from the country under President Manuel Roxas.

Araneta also fought against the Bell Trade Agreement with the same intensity.

Parity rights gave Americans equal rights with Filipinos to acquire public utilities and natural resources. Araneta could not find any justification for this inequitable privilege. Under no condition should we give these rights to Americans or other foreigners. He said “these are Precepts We Can Not Surrender.”

He further emphasized that, “Neither can we give away our sovereignty rights nor the patrimony of the nation.”

The Bell Trade Act, passed by the United States Congress, provided the continuation of the free trade of American goods entering the country but with initial and increasing limitation on Filipino products entering the United States.

The Bell Trade Act also pegged the exchange of the pesos to the dollar at the rate of two to one.

Araneta explained further why it was the “onerous currency obligation of the Bell Trade Act.”

Under this Act, the Philippine Government assumes, the obligation of producing and delivering dollars, one dollar for every two pesos delivered to it. Moreover, our government agrees not to impose any restriction on the transfer of funds from the Philippines to the United States. “They are indeed most onerous that could cause the bankruptcy of our government.”

Araneta asked the following questions: Did our government have the means and the facilities to live up to those obligations? How can the government guarantee that for the long period of twenty eight years it will have sufficient dollars with which to pay at the rate of two to one all the Philippine currency that might decide to leave the country? Would any government in the world assume such an obligation?

The Bell Trade Act also demanded that unless the Parity Rights were given to Americans, America would not pay war damages in excess of five hundred dollars. The implementation of the Bell Trade Act in a country so devastated by World War II would further impoverish its citizens.

Araneta was right. In three years’ time, the country was bankrupt. Recalling those days, Araneta said: “Those were the days when I was called names. I was referred to by President Manuel Roxas as a ‘prophet of disaster’ because I raised my voice against the Bell Trade Act. I was considered Anti-American, and regarded as an irresponsible experimenter of the people’s livelihood because I advocated import controls, a selective free trade with the United States, and the untying of the pesos from the dollar.”

Araneta felt vindicated, “I am happy to see that my views have at last received the protective mantle and authority from no less than Miguel Cuaderno, the Governor of the Central Bank.”

As to the charter of the Central Bank, Araneta added that Roxas did not dare create the Central Bank until it was proposed by the Joint Philippine American Finance Commission in 1948. (To be continued)/PN