BY DOMINIQUE GABRIEL G. BAÑAGA

BEYOND colorful masks and joyful parades lies a somber chapter from the past.

As Bacolod City celebrates the annual MassKara Festival, it is essential to reflect on the deeper layers of its history — a story etched into the core of Bacolod, one that cannot be forgotten.

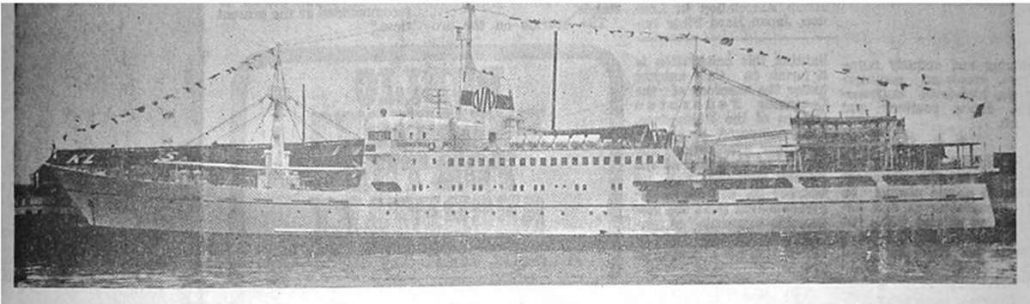

The M/V Don Juan

Offering a lifeline between Manila and the Negros province, the M/V Don Juan was a symbol of luxury and convenience. The Don Juan was more than just a vessel; it was a home on the sea, a connection between loved ones, and a testament to human ingenuity.

Built in 1971 by Niigata Shipbuilding & Repair Inc. in Niigata, Japan, the ship was launched on June 25, 1971 and completed and delivered in September of 1971. This liner was the longer and more powerful sister ship of the earlier Doña Florentina (launched 1965) and the Don Julio (launched 1967). The three were cruiser liners, rather than roll-on/roll-off ships and had cruiser sterns.

According to a research by Mike Baylon, founder of the Philippine Ships Spotters Society, the Don Juan a source of pride for the region, with its speed and size making it the flagship of the now defunct Negros Navigation.

The ship had a steel hull with a raked stem. She also had two masts, two passenger decks and an amidships smokestack. Her original capacity was 740 passenger, but she was later renovated to accommodate around 810 passengers, one of the highest then.

The ship was also one of the most technologically advanced in the Philippines during the period, equipped with radar, fire and smoke detectors, and automatic warning devices. She was also fast for her time, with the vessel doing the Bacolod or Iloilo route in 18 hours only.

Just as she was described, the Don Juan was comparable to a holiday cruise ship as she has dining rooms, air-conditioning in first-class accommodations, cabins, lounges, and dining salons.

Passengers can enjoy video tapes being played on television sets in the dining rooms. Games were also available onboard and there were sun decks and lounging spaces for passengers could see the seascape during its voyage.

During her service, Don Juan sailed twice a week from Manila at the start, one a Manila-Bacolod-Iloilo route and one Manila-Iloilo-Bacolod. Near her end, she sailed the Manila-Bacolod-Iloilo route twice a week on Tuesdays and Fridays.

According to Baylon, Don Juan departed Pier 2 of the Manila North Harbor at around 1 p.m., and if on schedule, she would arrive in Bacolod at around 7 a.m., and in Iloilo just before lunch time.

The tragedy

The M/V Don Juan met its tragic sinking one fateful night in 1980. Her collision with the tanker Tacloban City left many lives lost and families forever changed.

On April 22, 1980, Tuesday, while on a Manila-Bacolod voyage, she was rammed by the tanker M/T Tacloban City, a Mariveles-built tanker of the Philippine National Oil Company (not to be mistaken to another passenger vessel owned by a rival ferry company.)

Based on accounts, the collision took place off the southwest tip of Maestre de Campo Island (Now known as the Municipality of Concepcion, Romblon province).

According to Baylon’s research, the vessel was off course from the usual shipping route as vessels heading for Bacolod City during the period usually pass east of Maestre de Campo Island.

The vessel was doing a “fast clip” after leaving Manila at around 1 p.m. of the same day, which means the collision happened sometime around 10 p.m., Baylon added.

Since the vessel was out of the route, chances of a fast rescue were slimmer.

I talked Baylon regarding his research, and he said upon checking the schedules then, there were no other ferry or container ships when the collision occurred.

“Reports say she sank in 10-15 minutes. No time to get life jackets or organized evacuation. In collisions where hull was ripped (the reason she sank very fast), there would be water soon in the auxiliary engines that power the lights,” Baylon said.

With the sea current in Tablas Strait connected with the exchange of water between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, it would mean that even if one is on a life jacket, they are likely to drift away from the collision area, he further noted.

Still as salty as the seawater

43 years on, the tragedy remains fresh in the memory of the survivors or the kin of those who lost their lives on that fateful day. It was a disaster for Bacolod and for Negros.

Among the passengers aboard the vessel included families or members of prominent figures in Negros.

It was also full of Negrense students who have recently graduated in the top universities in Metro Manila, and were returning home to spend the summer vacationing with their family prior to beginning their new lives.

Among those who were killed include the Alunan family; the mother of lawyer and incumbent Bacolod City Councilor Renecito Novero; as well as the family of then Bacolod City mayor Jose Montalvo.

Montalvo lost his wife Nora and two of their daughters Mylene and Yvette, as well as his mother-in-law Anicia Kilayko.

The mayor himself was reported to have been so distraught that he even traveled as far as Romblon and Oriental Mindoro to look for his missing family.

Commodore Dannyl Yap, commander of the 618th squadron of the Philippine Coast Guard Auxiliary, was one of the surviving kin of those who lost their lives in the tragedy that I managed to interview.

Yap, who was only six years old at the time, lost his mother in the tragedy.

Although far from the ship when disaster struck, his life was forever marked by the loss of his mother and when he shared his story, it mirrored the collective pain and grief experienced by the families of those who perished, which carries on until today.

He recalled the shock and the uncertainty that enveloped his family as they awaited.

According to him, he was at his grandmother’s and uncle’s home in the town of Pontevedra in Negros Occidental when they heard the news over the radio.

The commodore’s mother was returning home to Negros after serving as a high school teacher in Olongapo City, together with his mother was his grandmother as well as two 2nd cousins.

Commodore Yap said her grandmother survived the sinking after she was spotted and picked up by a small boat.

“Ang lola ko hambal nya last nya nakita nag bulig pa ang akon iloy tungod nga kabalo to sya lumangoy, [My grandmother said she last saw my mother, who knew how to swim, helping other passengers] ” the Commodore said. “Si lola ko ya survivor, tungod nag lumpat sya sa tubig, and nangamuyo sya ‘Diyos ko may kabataan pa ko,’ [My grandmother survived after jumping off the the water and prayed the whole time ‘Lord, I have children who needed me’]. Those were her words that I will never forget,” he further stated.

The remains of Yap’s mother was later recovered by authorities; he even recalled that argument arose between their family and the family of another victim when claiming the remains.

Fortunately, Yap said the matter was resolved quickly thanks to the municipal officials of Pontevedra who also arrived in Iloilo to claim the remains of the town’s residents who lost their lives in the tragedy.

His family’s experience, like that of so many others, serves as a reminder of the profound impact the M/V Don Juan tragedy had on the lives of those left behind.

It is a shared grief that unites the community in Bacolod, not as survivors but as those who bear the legacy of the past.

The MassKara Festival, as Yap explains, is not a direct commemoration of the tragedy itself.

He believes that the MassKara Festival is a celebration of life and a testament to the city’s ability to bounce back from adversity, the strength and determination to turn pain into positivity.

It represents the triumph over difficult times, including the economic hardships faced by Negros in the 1980s. The festival is a symbol of resilience, unity, and unwavering smiles.

The sinking of the M/V Don Juan also reminds us of the fragility of life and the importance of cherishing every moment.

It teaches us to honor the past while celebrating the present. The MassKara Festival is not about commemorating what was lost, but rather about reveling in the vitality of Bacolod City and its people.

In the words of Commodore Yap, “Human error is more dangerous than mechanical error.”

We must take this wisdom to heart as we remember the tragedy while rejoicing in the spirit of the MassKara Festival.

This annual celebration serves as a reminder that, in the face of adversity, the people of Bacolod continue to smile and embrace life, turning their sorrow into strength.

The MassKara Festival symbolizes their resilience, celebrating life even in the face of adversity and loss./PN