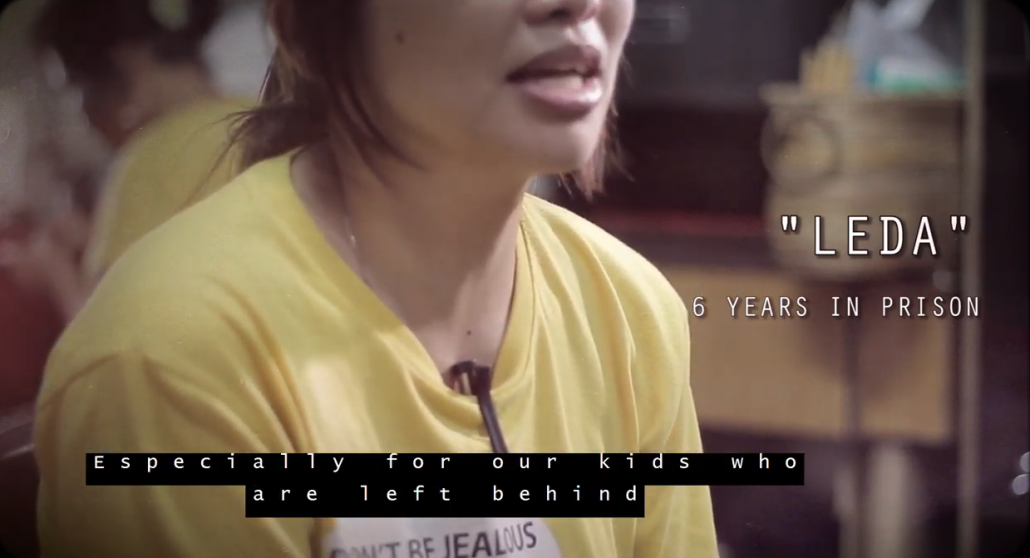

ILOILO City – “Indi lango-lango ang sitwasyon namon diri sa sulod, especially if may bata ka sa gwa,” shared Leda, a 41-year-old mother of three who has been in jail for six years already. “Wala sang minute nga indi namon sila ma-miss.”

Leda is an inmate at the Female Dormitory of the Iloilo City District Jail, among 220 packed like sardines in 133 square meters of space (about half a square meter of floor space for each inmate).

She is also one of the 150 women inmates who have been lent a voice amid their harrowing conditions by the Hilway Art Project and the “Lullabies in Prison,” a short documentary that shed light on the initiative – projects that provide the public a view of how mothering continues even behind cold steel bars.

“These women are in an unthinkable situation,” said Hilway Art Project curator Ma. Rosalie Zerrudo, an assistant professor at the University of San Agustin’s Fine Arts Major Organization. “Think of a cell that is supposed to house only 30 people [but] occupied by 230 women.”

“These women are on trial,” said Zerrudo. “We’re not talking about [being] on trial for just, say, five days. We’re talking about five years, 10 years.”

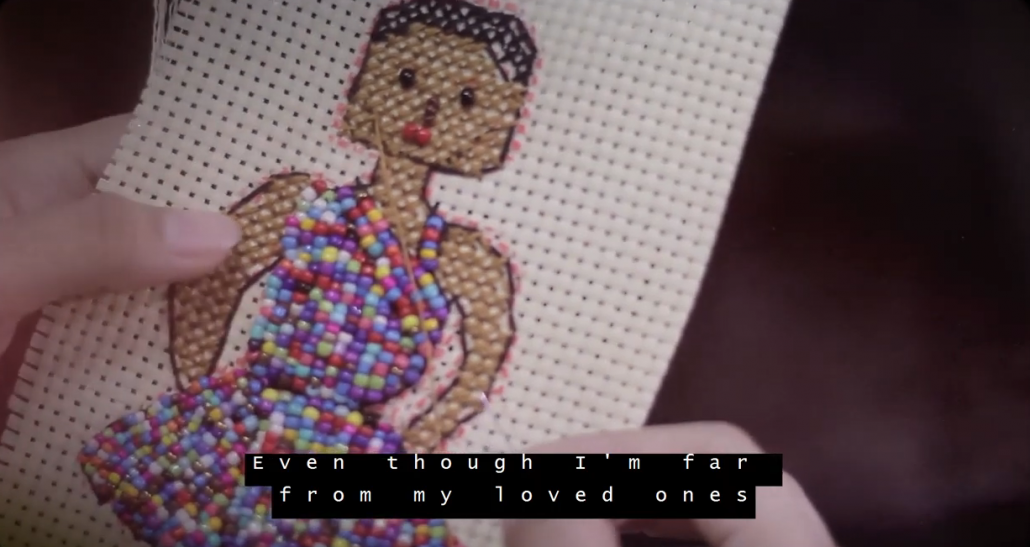

According to the professor, Hilway started with art workshops and interviews with the women inmates. “I discovered that they can actually create very great art, [making dolls out of fabric and beads], and so Inday Dolls were born.”

These dolls soon landed on the documentary that Ilongga filmmaker Ethel Mae “Mia” Reyes made through a grant from the Philippine Center of Investigative Journalism Story Project.

“I focused on the Hilway Art Project, which provides 150 women inmates opportunities for livelihood and art therapy,” said Reyes.

The women inmates make what they call “Inday dolls” out of fabric. “Each of the dolls comes with a favorite quote of the maker, and they are sold in trade fairs, pop-up shops and online,” said the filmmaker.

According to Zerrudo, these “iconic products” tell the women inmates’ “personal narrative … their pain, their struggle, their anxiety, their dreams, their hopes, the stories of their families.”

“The women then started to write their own hugot – you know, angst – kind of their shout-out to the world, and their messages were very powerful. We decided to [put] these [on] the dolls as tags,” she added.

The ICDJ Female Dormitory is right at the heart of the city, tucked away in the compound of the Iloilo City Police Office along the busy General Luna Street, right across the University of San Agustin. It was built for 28 inmates.

When the number of drug crime detainees racked up after Congress passed a comprehensive law against dangerous substances – and, more recently, when the Duterte administration launched a fatal crackdown on drugs – many jails across the country, including this one, got overcrowded.

“Nearly all the women in the jail have been accused of drug-related crimes,” said Reyes. “Except for two who have been convicted, they are all awaiting trial in the city’s slow-moving and understaffed court system.”

Citing a jail official, Reyes said women there stay an average of five years “because court dockets are packed and there are not enough prosecutors.” Some of them are incarcerated for 10 years before getting sentenced, she said.

“Many of the inmates are mothers who long for their children,” the filmmaker said. “What struck me was how they kept their dignity and humanity. They were gracious and generous. They were also neat and well-groomed. Some did regular manicures and pedicures. They were wearing makeup when I filmed them.”

“Lullabies in Prison” features women inmates engaged in the Hilway Art Project. “Their ages range from 18 to 69 years old, and most of them are mothers with young children. Their identities were concealed to protect their families, who they love and miss,” said Reyes.

Hilway – a result of a two-year collaboration with more than 200 women inmates – involved 74 women in the “Hugot sa Punda” embroidery project, 85 in the hand-embroidered beaded soft sculpture “Inday Dolls,” 25 in painting, and 22 in accessory design and production.

As a direct psychosocial support for women in the ICDJ Female Dormitory, where 91 percent of the inmates are facing drug-related cases, Hilway hopes to contribute to drug rehabilitation through art.

Some of the participants were breadwinners who continued to mother behind bars.

“Sa muni nga mga doll, biskan ari ko di masarangan ko tanan nga mga problema nga gaabot sa akun, biskan layo ko sa pamilya ko,” one of the inmates said in the documentary.

“This design simbolo ko sa akon bata para diri ko makita kag mabatyagan ang iya tsura para di ko mahidlaw,” another shared.

“Ang akun design ginahalimbawa ko sa akon bata nga sia lang gahatag sa akon kusog kag kabakod biskan ari ako sa prisohan,” explained a mother longing for her child.

“Ang doll nga ni gin-obra ko para sa bata ko sa Mindanao nga wala ko na nakita. Wala sia kabalo nga napriso ako. Diri ko na lang sia makita sa doll nga ini. Wala sia kabalo sang natabo sa akon, indi ko na sia ma-contact,” related an elderly inmate as she helding back tears.

“Sa adlaw-adlaw damo kami ginapaminsar kag ginapaligban nga kon ano-ano lang, pero kon kaobra kami cross-stitch, daw gakahagan-hagan kag gakalingaw kami,” said another.

Reyes, who also teaches fine arts at the University of San Agustin, thought anyone living in a cramped and confined space for years would be like caged animals, vicious and violent – until she knew the women at the ICDJ Female Dormitory. “I was wrong,” she said.

According to Leda, Hilway has become a part of their daily lives.

“It helped us a lot, especially with our financial needs. Mostly mothers kami diri kag we are still supporting our kids sa gwa,” explained Leda. “We have learned a lot in this project, and it has helped us with our talent and skills. The Hilway project has helped us become better persons.”/PN