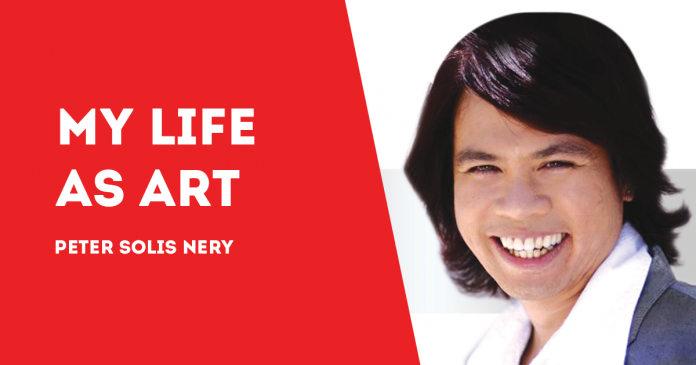

THIS IS the first part of Peter Solis Nery’s 2013 Palanca award-winning story “Si Padre Olan, and Dios kag ang Ulan” translated by retired UPV Professor Celia F. Parcon, winner of the 2020 Peter’s Prize for Excellence in Literary Translation.

*

Father Olan, God, and the Rain

By Peter Solis Nery

Translated by Celia F. Parcon

*

First came Don Beato Yngala who owned the vastest of rice lands in the whole town of Buenavista. On the Tuesday before the feast of St. John, he arrived at the conventin Navalas to visit with Father Roland Divinagracia who went by the nickname Padre Olan. The priest invited him to breakfast. It was not even nine in the morning, but already it was steaming hot. The sun shone fiercely like it was out to burn. The don, in a thin white shirt with long sleeves, was sweating profusely but not from exertion. Padre Olan was perspiring too, but not from awe or fear of the don. It was just that the weather was really hot. The dripping sweat caused the priest’s shirt to stick to his shoulders and chest. He wiped himself with a handkerchief.

Because of the intense heat, the priest had breakfast served in the garden behind the convent. A hut stood in the middle of the flower garden. Except for the verdant bougainvillea, all the plants were wilted and dry from the extended and terrible heat. The last of the rains had come in October; it was now the middle of June. El Niño had struck again.

On the concrete pathway leading from the kitchen, the priest noted that the soil had dried up on both sides of the plot where azucenas—the Polyanthus lilies, and African daisies bent dying. Out of extreme dryness, the cracked earth gaped like a mouthcrying up to the heavens for rain.

The thermometer hanging from one post of the hut read 43 degrees Celsius (over 109 degrees Fahrenheit), but no one noticed. The priest only felt the biting heat from the rays of the sun.

There was not a single whisper from the breeze in the garden, yet it was cooler in the shade of the little hut than in the convent’s dining room that was hot on days like now when power was out and no electric fan could cool the room.

Nang Paquit, the cook, served the priest and the don. The priest had pork sausages, eggs, and fried dried milkfish on Tuesdays. There was pale watermelon and scraped fresh coconut on grated ice. Nang Paquit also put some coffee on the table in the middle of the hut but neither the priest nor the don even touched it. The heat was just unforgiveable.

“Father, if the rain doesn’t come, we shall all go hungry. How can we plant if the rains don’t come? How can we harvest if we can’t plant? Where shall we get rice? How can we eat?”

One after another the questions came from Don Beato, a trusted man in the town and a pillar of Buenavista, and frequently a sponsor of many of the church’s needs. Even while his coming to the priest seemed like it was because he was concerned for all, Padre Olan knew that it was really only interest for his own business that pushed the don to come to him.

Don Beato Yngala was a frequent churchgoer but he was not known to be a religious man. He doesn’t join in the singing during Mass, nor does he recite the Catholic Nicene creed.

“We’re not the only ones suffering from this El Niño, Don Beato. The situation is worse in Luzon. The Magat Dam has dried up, and so has the irrigation in Isabela, Cagayan, Nueva Ecija, and Nueva Vizcaya,” explained the priest in an attempt to calm down the don who by now was sweating in beads as large as berries.

“Irrigation on our entire island has dried up too, in case you didn’t know,” replied the don with slight arrogance.

“So what would you want me to do now, Don Beato?” asked Father Roland Divinagracia.

“What if we prayed?”

Padre Olan could hardly believe what he heard. But he was glad. Don Beato, inviting him to pray?

“Okay. Let me have these dishes put away. Then we can pray,” the priest quickly replied.

“What I mean,” said the don awkwardly, “…in church.”

The priest was more surprised. His face lit up. He smiled. He seemed to understand the don. “Don Beato,” Padre Olan clarified, “God will listen to our prayer, no matter where we are. We don’t have to be in church in order to pray.”

Don Beato took a deep breath. “Father, what I really mean is, if possible, that the entire congregation will pray… this coming Sunday. Instead of celebrating the feast of Saint John, why don’t we set aside a special day of prayer for rain?”

Padre Olan was shocked. It took a little while before he could speak. When his voice finally came out, it was in the form of two questions.

“Are you talking about a special day just to pray for rain? And for that to replace the celebration of the feast of St. John?”

The don nodded.

The priest shook his head. “Don Beato, that is impossible. We follow a calendar of masses to celebrate the feasts of the saints.”

“Are you refusing? Coming up with excuses? Why is it not possible?”

“Don Beato, we can include in the Prayers of the Faithfula petition for rain. I don’t see a need for us to change the entire liturgy just to beg for rain.”

“And why not?” the don’s voice hadn’t lowered a bit. “Of what use is the Mass or the liturgy if we should go hungry? I tell you, Father, famine will be upon us if the rains don’t fall in the coming days.”

Don Beato Yngala’s blood boiled as he left the priest in the hut in the middle of the garden. He was not used to being denied anything.

Padre Olan Divinagracia’s face also heated up, but he understood the arrogance of the don who owned the vast fields that now in mid-June were still not planted. (To be continued/PN)