BY DOMINIQUE GABRIEL G. BAÑAGA

WHEN I was around six years old and was in first grade in an elementary school in Iloilo City, I always kept wondering about the statue that stood between the gate of the old Muelle Loney Port and the Iloilo Customs House.

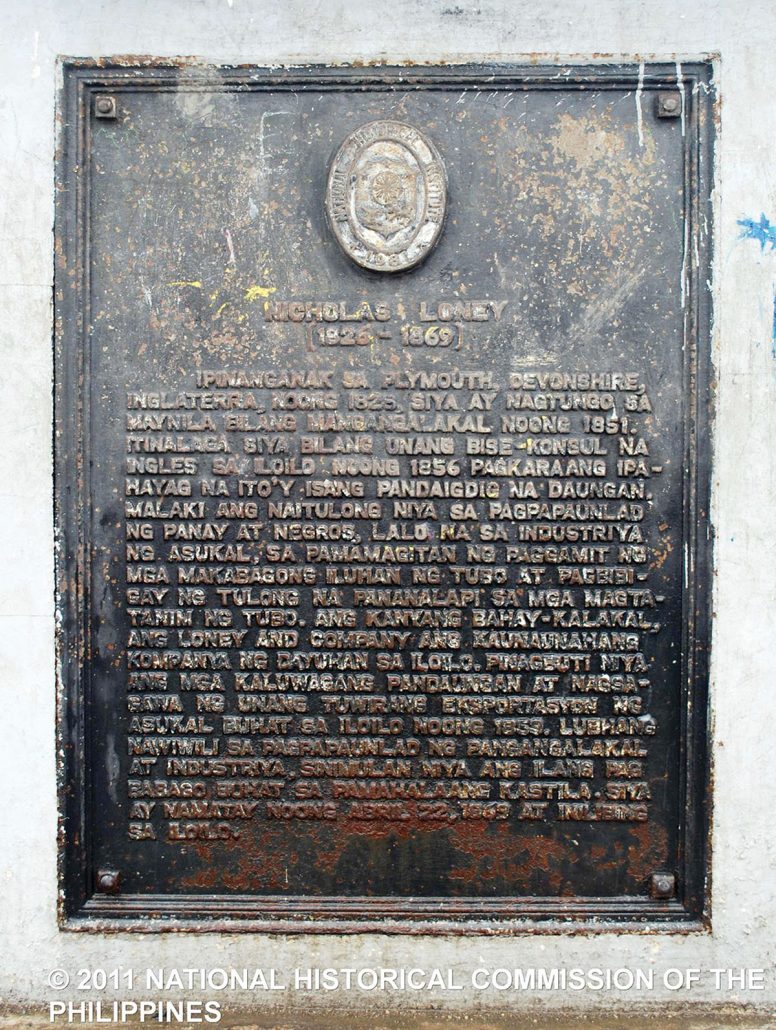

Statue of Nicholas Loney in the area named after him, Muelle Loney. PN PHOTO

It was only when I got older that I realized that the statue, standing in the area to this day, was the namesake of the port which previously hosted the ferry terminal and fastcrafts bound for Bacolod City – an Englishman named Nicholas Loney.

Loney was born in 1826 in the port city of Plymouth in the United Kingdom.

During Loney’s birth, Plymouth was already known as a commercial shipping port, and was also the home to the world’s greatest naval force at that time, the British Royal Navy.

Nicholas was the son of Robert Loney, an admiral of the Royal Navy. He also had nine siblings, and even though Robert was a top British naval officer, the Loneys were not particularly regarded as a “well-to-do” family unlike other British military officers at the time who may have only gotten to the ranks because they were either part of the British aristocracy, or if you are rich, able to buy your own officer’s commission.

Even though Nicholas’ formal education would only be limited to attending grammar school, he still showed great knowledge based on his letters and consular reports.

In 1842 at the age of just 16 years old, Nicholas left for the South American country of Venezuela, where he ultimately became fluent in the Spanish language.

Nicholas stayed in Venezuela for four years before going back home to England sometime between 1846 and 1847.

After staying for a year in England, he again left his home country and traveled to the British-colony of Singapore.

While in Singapore, he heard of the growing Manila trade and applied to Kerr & Co, a British firm with offices in England, Singapore, Manila, and Batavia (present-day Jakarta, Indonesia).

By 1851, Nicholas moved to Escolta Street in Manila after being appointed to the firm’s correspondence department.

Nicholas immediately took a liking to the Philippines and during his downtimes he would travel outside of Manila and because he was fluent in Spanish, he had little difficulty making friends either with the local Filipinos or the Spanish colonials.

Muelle Loney, circa 1910-1920. PHOTO FROM THE PINTEREST ACCOUNT OF MAY WOOD

A photo of Englishman Nicholas Loney courtesy of the University of the Philippines-Visayas Center for Western Visayas Studies

By 1855, he became in charge of the firm’s Manila office, alongside Scottishman Robert Jardine, who would later become the head of the Jardine, Matheson and Co., one of the largest British Far East trading houses based in Hong Kong.

Later that year, Nicholas resigned from the firm and planned to return home to England, but this was thwarted when in September of that same year, the British government approved the opening of three more ports for foreign trade – Sual in Pangasinan; Zamboanga in Mindanao; and Iloilo.

Nicholas, a favorite among the British merchants in Manila, was immediately nominated and appointed by the British as their vice-consul in Iloilo on June 11, 1856.

During his appointment in Iloilo, the export of sugar was highly-encouraged by both the British and the Americans, and by around the 1850s the Spanish-controlled Philippines was already exporting 29,090 tons of sugar.

At the time sugar was also a rising industry, especially in Central Luzon, although it was still a developing industry in Iloilo and Negros island.

Upon his arrival, Nicholas immediately got to work ordering the construction of a building for the vice consulate and since it would take some time before it could be completed, he decided to rent a house near the Jaro town plaza.

One of Nicholas’ objectives was to promote direct trade between Iloilo and foreign countries, particularly in Europe, where sugar was in great demand.

He also began bringing in goods from Manila and putting them for sale in Iloilo, although this wasn’t noted to be of a success.

In 1857 in order to meet the growing demand for sugar, Loney started visiting towns in Iloilo and also visited Negros Island. He would ultimately become greatly impressed by the soil’s fertility, particularly in Negros, which at that time, was practically still a “virgin land.”

Loney immediately developed the sugar industry by providing farmers with loans so they could start their farms.

He also imported technology, equipment, and European expertise in order to improve sugarcane milling, thus ultimately modernizing and helping launch Western Visayas into the Industrial Revolution.

The “Sugar Rush” as it would be called will transform Negros from a “sleepy” island into the top sugar producer in the country, a title still held by the island to this day.

Many Iloilo families immediately moved to Negros, starting their own haciendas, and Nicholas even built his own hacienda near Matab-ang River in present day Talisay City.

Nicholas’ hacienda is now owned by the Lacson family.

Meanwhile, Iloilo was transformed into one of the major sugar trading posts in the country. Sugar being produced in Negros would be transported to Iloilo, and from there it would be exported to other countries.

Nicholas also started his own firm called Loney & Co, the first foreign commercial company outside of Manila with the primary purpose of importing goods from Manila and selling, or trading them in other nearby provinces such as Antique, Negros and Leyte.

In 1866, Nicholas moved back to Manila after being appointed as acting British consul. He left behind the management of his hacienda to the hands of his brother, Robert.

A year before, Nicholas married Leontine Traschler in Hong Kong, and by the time he moved to Manila he already had two kids, a son and a daughter.

While in Manila he proposed a series of reforms to the Spanish authorities to further promote economic growth and encourage trade.

In 1869, Nicholas and his family moved back to Iloilo, although by this time, he and his wife were already thinking of returning to Europe, with Nicholas aiming for the position of vice consul in Spain.

While at his home in La Paz, Iloilo he also started to conceive a plan to climb up the Mt. Kanlaon volcano to further explore possible agricultural and scientific developments.

Sometime between April 17 and 18 of 1869 as they were in the middle of their expedition in the volcano, Nicholas suddenly fell ill.

His fellow companions in the expedition later decided to bring him down to his Matab-ang Hacienda as his condition was deteriorating, but sadly on April 23, Nicholas died aged only 43 years old.

To this day, it is unknown as to what disease killed Nicholas.

Nicholas was buried at the shoreline facing Point Bundolan, Guimaras, now present-day Rizal Street, Iloilo City.

Nicholas’ statue on Muelle Loney was unveiled in March 1981, and to this day Ilonggos and Negrenses are still thankful for his contributions which helped catapult both Iloilo and Negros into the modern era./PN