WHILE generally art produced in the regions (outside of Metro Manila) has been embraced by the so-called mainstream art market, some talents from the regions still fail to get as much attention from the culturati or the art market as the award winning artists have. Ronnie Granja is one of them.

Granja (born 1964), like most Ilonggo artists, is not educated in the rudiments of the fine arts. He is self-taught. He finished Architectural Drafting from The Iloilo School of Arts and Trades (now Iloilo Science and Technology University). The program along with the bachelor’s program in Architecture is the closest option budding artists in Iloilo enroll in to get some art-related training. Eminent ceramist Nelfa Querubin was a graduate of the program.

But while Querubin ventured to Manila to look for a regular job along with the desire to hone her talent in the visual arts and make a name for herself, Granja chose to remain in Iloilo. He would occasionally join national art competitions; sometimes he succeeded: Honorable Mention in the 1999 Letras y Figuras competition of Instituto Cervantes of Manila, Finalist in the 2001 Philippine Arts Awards, Honorable Mention in Painting in the Art Association of the Philippines (AAP) Annual Competitions in 2003. Eventually he returned to his hometown, Dingle, to teach in the arts program of the high school there. He has mentored students who won in student art competitions in painting or poster-making in the region and beyond.

Granja dabbled in abstraction; some were successful, some were not. But in the successful ones, he demonstrated that he was adept at manipulating colors and shapes to maximum aesthetic advantage. His series of watercolor paintings of nudes show a considerable level of mastery in handling such difficult medium even as they make one remember Matisse and fauvism.

In the 1990s when he was living in a boarding house as a student and as a fresh graduate doing odd jobs in the city, he created a series of paintings about it. In that series, cramped living and sleeping quarters with human figures lying in bed, writing letters, combing their hair and such congest the pictorial spaces.

Humanity and the human condition along with a sense fairness and justice appear to be major concerns for Granja. While yet struggling to master painting techniques and trying our various aesthetics, Granja was already exhibiting thematic constancy – proof that he has what it takes to be a serious artist eventually and was not just a hobbyist.

Granja is gregarious. He lacks the apparent angst-filled persona of most of his kind although he fits naturally well into the physical stereotype of “the hungry artist.” He is upbeat and jolly while occasionally displaying irritation rather than anger over wrongs. A natural raconteur, Granja is full of stories about his life and circumstances and anecdotes regarding the local art scene and artists. These stories are often distilled and filter into his more significant works all these years.

In his ongoing show at Museo Iloilo (until Jan. 21) titled “Rubo-rubo,” a Hiligaynon term that signify an innate capability to do any kind of work to survive, Granja seemed out to prove that he can work on any kind of art that he wanted to stay afloat as a professional artist. This might be quite a naïve way of looking at serious art making but this is consistent with Granja’s innermost character as an artist who has struggled much socially and economically. The title serves well the contents of the exhibition. His works in this exhibition span almost three decades. What is generally obvious about the works presented in this second solo exhibition of Granja’s is the artist’s experimentation with technique and style in the quest to find his own voice as it were.

Immediately upon entering the museum, one encounters “Hall of Faith” (2011), a sort of self-portrait, which depicts a conflicted individual who is torn between the proverbial forces of good and evil. While this work is very stark in content and intentions, its overall technical appeal is rather labored or contrived; its colors are dull denoting sadness. But the very personal allegorical details found on a blend of Egyptian and Greek architectural portions are well-crafted and absorbing. While this may not be the most attractive painting in the show, it is what requires the most scrutiny to be appreciated. The artist revealed that this work was made at the time when he was desperate for money to his third child’s hospitalization.

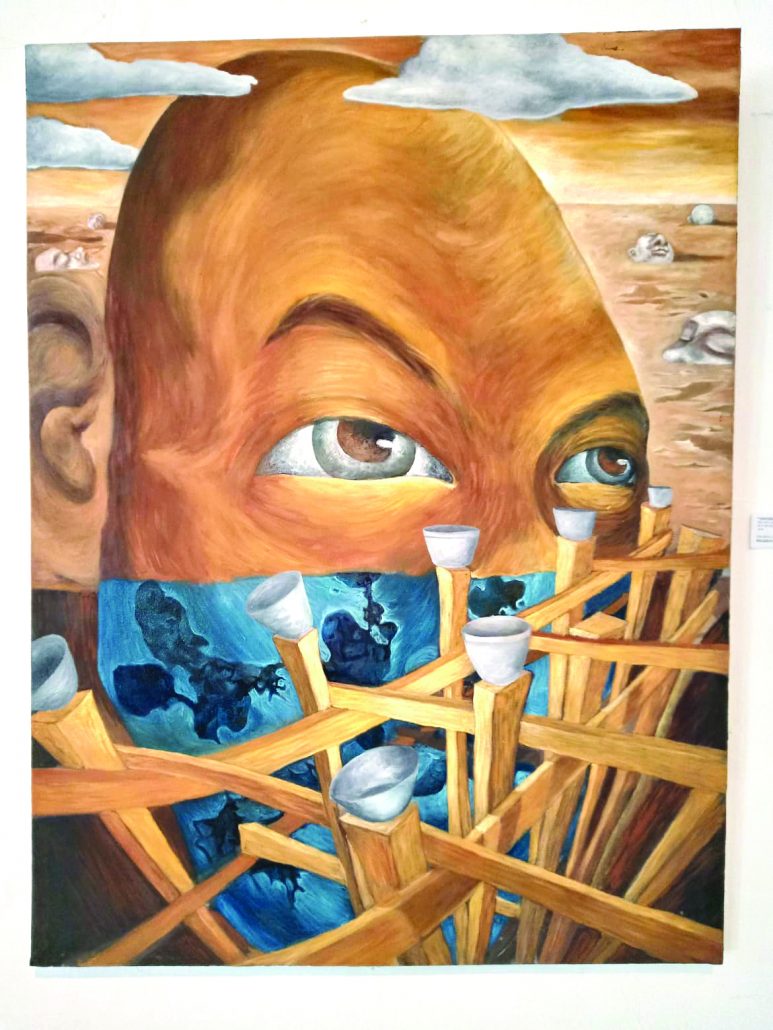

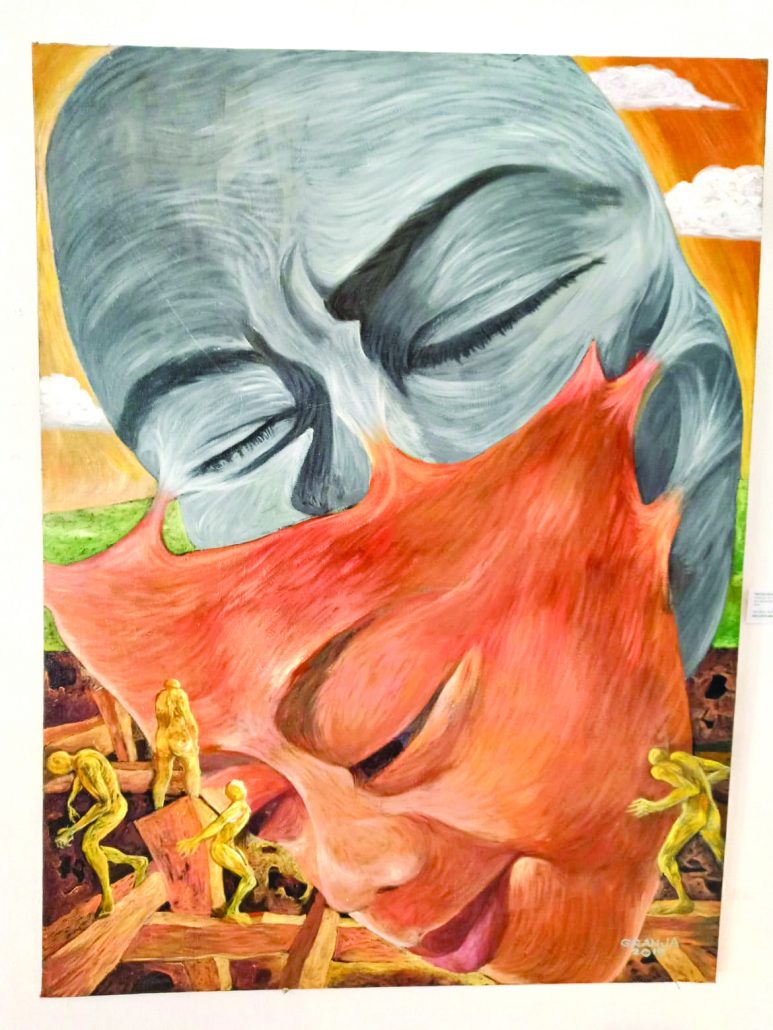

“One Way Feeding Program 2” (2019) along with some other earlier paintings about boarding houses show traces of the style, particularly the reuse of elongation reminiscent of El Greco’s works, compellingly harnessed by members of the Saling Pusa artist group in their collaborative and individual works. This, however, should not be immediately taken as a point against the Granja because unlike the artists in the said group, his concerns are rather local, personal and intimate not categorically national or global. While the works of the former are tiptoeing the thin line separating propaganda and social realism, Granja’s paintings “Abandonado 1,” “Abandonado 2,” “Balatian,” “Baliskad,” and “Kamaturuan” all done in 2019 are at once metaphoric and very private with only the titles vaguely hinting at the larger narrative they depict or the inspiration they may have been sourced from.

In these surreal paintings, also, one may submit that Granja has chanced upon a style which has veered away from his previous strong influences and references. The paintings that show grotesque and rounded human figures and faces in bizarre environments and circumstances and employ luminous colors display the artist’s technical proficiency and assert his visual expressiveness. These paintings’ composition is consistent. The use of a single looming central image along with smaller-sized characters and details in the intended narrative of each of these paintings reiterates hierarchical scale. In these works that comment on inequality, hypocrisy and other social ills and represent the artist’s frustration, rather irritation, with the systems that are at work in society and his workplace, it is not exactly an exaggeration to say Granja has found his aesthetics.

At this time, Granja may need to reassess his artistic direction and drop the desire to prove that he can do any kind of art style to fit the demands of the art market to meet his personal needs. At this point, he may have to rise above the “rubo-rubo” mentality of a laborer and proceed to work on what is personally or spiritually gratifying to him and worthwhile of his considerable skills as a painter. (Martin Genodepa/PN)