THROUGH collective action, environmental protection can be achieved. This is what the Kalinga indigenous people in the Philippines demonstrated to the world when they stopped the famous Chico River Dam Project from being constructed, and it is what inspired Joan Carling to make her lifelong mission fighting for human rights in land development.

“In the very principles that indigenous people carry, it says that we must retain our reciprocal relations with Mother Nature,” says Carling who is from the Kankanaey tribe in the Philippines. “That reciprocal relationship is the one that I believe is being undermined by the western concept of development.”

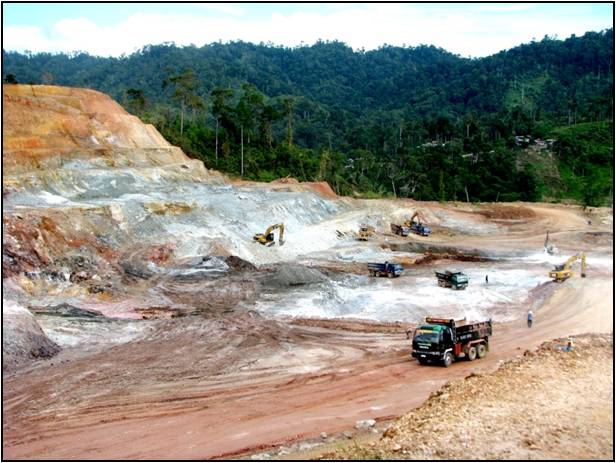

Carling, 55, began her career as an activist more than twenty years ago in Cordillera, a northern region of the Philippines. The area, which is home to 1.3 million indigenous people, sits on the country’s mineral belt – rich in gold, copper and manganese.

The country’s Mining Act of 1995 allowed transnational corporations’ total control of the mineral-rich lands including full water and timber rights and even the permission to evict communities from approved areas.

So Carling, along with others from the Cordillera People’s Alliance, began to gather information on the impact of mining as evidence to use to petition the government. She says that the reason the alliance was able to stop some of the planned projects from happening is the evident impacts on the natural environment, such as the polluting chemicals in rivers. After a unity pact was signed by elders from all provinces to oppose mining companies, a provincial governor also vowed a no-entry policy on mining operations in his district.

“It became clear that unless people on the ground took action, politicians would not be held accountable,” Carling said.

Carling – like her indigenous predecessors – has also spoken out against dam building. While she acknowledges that many people see dams as a renewable source of energy, she says that not only have they destroyed many river ecosystems around the world, they have also led to human displacement.

A recent study by the University of Sussex and the International School of Management in Germany found that countries that rely on large hydropower dams for their electricity suffer higher levels of poverty, corruption and debt compared to other nations.

“It’s become clear that there is a bias for dams because there is a huge profit generated by dam builders, a huge opportunity for corrupt officials to put money in their pockets. That profit is driving the dam business, more than responding to needs,” she said.

Still, many developing countries consider dam construction as an expressway ticket to economic development. Carling knows this, and that’s why she has not outright advocated for a ban on dam projects, but “a human rights-based approach to energy development”.

“Indigenous peoples are not the enemies. We are not against development,” she said. “But one of the strongest recommendations by the World Commission on Dams is for countries to do an options assessment in relation to energy needs. There are different options, it’s not only dams.”

That is why Carling is exploring new territory: partnerships with the private sector. She hopes that by collaborating with environmental champions in business, they can help show sustainable development is possible.

Carling was bestowed with UN Environment’s Champion of the Earth lifetime achievement award in 2018. (With UN/PN)